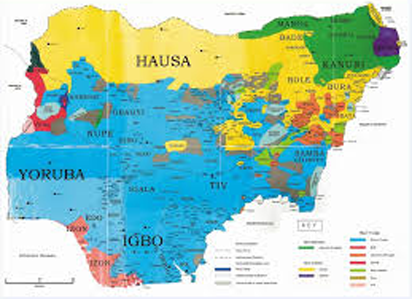

Map-of-Nigeria

By Hakeem Baba-Ahmed

I published this material almost exactly ten years ago. If you read it, you will see that it was a lamentation over the state of the North as I saw it in 2013. A friend, Abdulrauf Aliu, drew my attention to it two days ago. Yesterday was the first time I read the material since it was published, and it disturbed me a lot. Now it sounded like a lamentation over a nation that had wasted a decade that could have made all the difference in its fortunes. Then I remembered that the rich and powerful have created a lot more poor people in Nigeria, and that the democratic process has empowered the poor to reverse the advantages that are stacked against them. Will the poor decide to put good, honest, and competent leaders in power with their votes, or will they waste the opportunity by playing into the manipulations of the rich and powerful? Do they know people who will be honest and competent leaders? Do they exist? If the good ones are squeezed out and life gets worse, what is the future of the democratic system in Nigeria? In the North, and in many other parts of Nigeria, people are asking what the value of voting is. In some parts, armed criminals say no one will vote. These forthcoming elections will also be a referendum on the democratic system. if they hold.

One day the poor will have nothing to eat but the rich— Anon

STATISTICS on poverty levels in Nigeria released by the National Bureau of Statistics have raised issues that can be interpreted in many ways, one of which is that Nigeria represents an alarming paradox. There are, as with all statistics, serious issues related to definitions of the poor, such as the index of $1 (N150) earnings, but all definitions tend to suffer similar or worse limitations. The value of statistics that highlight poverty at individual, household, regional, or national levels is essentially as guides in highlighting the complexities of social existence, and as values that can be deployed towards developing policies for political and economic development.

It is important to pay attention to them, although policymakers and politicians tend to welcome or dismiss them according to the manner in which they hint at the standards of or the quality of their governance. At a time when Nigerians are bombarded with staggering figures released (and largely squandered) to states in the South-South or much smaller sums frittered away by governments in the North, it is critical that we do not dismiss these statistics.

According to the statistics, Sokoto State is the poorest state in Nigeria, with a poverty rate of 81.2 per cent. Katsina is second with 74.5 per cent, followed by Adamawa with 74.2 per cent, Gombe with 74.2 per cent, Jigawa with 74.1 per cent, Plateau with 74.1 per cent, Ebonyi with 73.6 per cent, Bauchi with 73 per cent, Kebbi with 72 per cent, and Zamfara with 70 per cent. States with the lowest poverty rates were Niger (33.8 per cent); Osun (37.3 per cent), Ondo (45.7 per cent); Bayelsa (47 per cent), and Lagos (48.6 per cent). Five of the poorest states in the North-West zone (out of the seven) are, therefore, the poorest in the country. The zone has an average poverty rate of 71.4 per cent.

The poorest region of the nation, the North-West zone, has a population of 35.7 million, 14 million more than the total population of the South-South, and almost 20 million more than the South-East. In fact, the North-West zone alone has about the same population as the South-East and South-South combined. The three Northern zones have a much larger proportion of the nation’s human capital, land mass, and agricultural assets, and they harbour its fortunes in solid minerals yet to be exploited.

If the right atmosphere is created, and appropriate policies are put in place, the north of Nigeria can feed the entire West African sub-region. It will earn 20 times what the nation earns from oil and gas in minerals and other natural resources, and save the nation trillions by developing and using renewal resources and energy. The paradox of the North lies in its potential for greatness, and the existence of unacceptable levels of poverty. Its huge and expanding population barely produces what it consumes; and it does not represent the large market it should because it has no purchasing power. Its economy is still substantially peasant, and its patchy infrastructure is decaying. Its young population has no hope of quality education or opportunities to acquire skills, so it will feed its poverty even more. It has no industrial base, no skilled labour, and no capital to invest in developing agricultural technology or its vast water resources. It has a large majority of the voting population, yet its political fortunes dwindle by the day.

For every university or polytechnic graduate, the region may produce 100 almajirai.It has some of the richest men in all of Africa, and the highest rate of VVF in Africa. It has the lowest success rates in qualifying examinations for post-secondary institutions, and the highest percentage of unqualified teachers in its primary and secondary schools. Its elite go to India, Egypt and Dubai for medical attention, while the vast majority of citizens do not have functional rural health centres. Its politicians drink expensive bottled water and spend millions on food every year, while millions of citizens lack access to safe drinking water.

The areas of growth in the North are population and insecurity. Families breed with scant attention to what lies ahead for their children. Insurgencies rooted in poverty and disenchantment with a decaying social structure threaten the poor, because the leaders and the rich are largely protected. Huge amounts are collected by government every month and spent on governments, not the people. Easy money breeds circles that feed on local politics while alienating the majority of the population. State institutions shrivel and atrophy, and the basic cycle of life is barely sustained.

Statistics will be disputed, and even the assertions above will be challenged by governments and politicians. Yet insecurity spreads; young people take to drugs and lend their limbs and lives to politicians, and the rest of Nigeria moves on as if the desperate situation in the North is not its problem. Life is a desperate drudgery for the vast majority of Nigerians, which they will pass on to their children. People in the South are desperately poor, despite the fact that trillions of dollars are available to help them. In the North, traditional fatalism is being replaced by anger and frustration at the failure of the state and the democratic system to make tangible differences in the lives of citizens.

Across the nation, anger and increasing poverty could combine to scuttle the gains made in efforts to give people a chance to improve their lives through their toils and the political choices they make. There is an opportunity to redress the weaknesses in the quality of governance and distribution of resources across the nation, if the leadership will even acknowledge that the problem exists.

Disclaimer

Comments expressed here do not reflect the opinions of Vanguard newspapers or any employee thereof.